by Asa Gordon

“The practical construction of American life is a convention against us. Human law may know no distinction among men in respect of rights, but human practice may. Examples are painfully abundant ” ~ Frederick Douglass

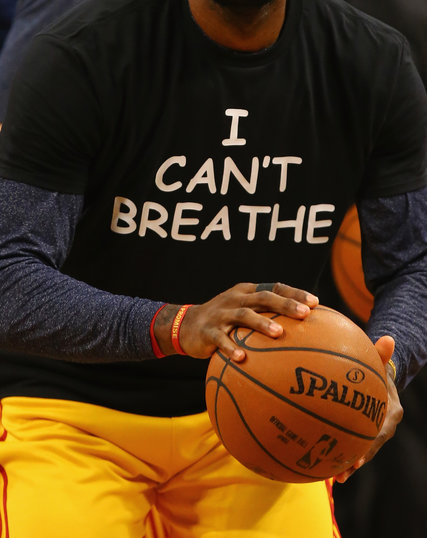

It is painfully abundant in the contemporary examples: #HandsUpDontShoot; #ICantBreathe; and #BlackLivesMatter. The problem is that there has evolved a consensus focus of Liberal and conservative pundits on a distorted vision that our broken judicial system does not value the view that “Black Lives Matter”. That astigmatized consensus is blind to our judicial systems’ historical legacy that systematically devalues the testimony of blacks that bear witness to white misconduct. The recent prejudicial presentation by prosecutors and the clearly astigmatic judgement of grand jurors in racially charged cases in Ferguson, Mo. and New York bears witness to prosecutors that devalue black life and grand jurors that devalue non white testimonity. The practical construction of American life may devalue black life before our human law, but it is our human practice of devaluing non-white testimony that bears witness to white misconduct against non-whites that denies justice, even when that witness is an inanimate camera.

In 1860, Frederick Douglass captured the astigmatic colorblind vision adopted by our contemporary prosecutors and grand jurors by observing that prejudice is “always blind to what it never wishes to see, and quick to perceive all it wishes.” Sociologist James W. Loewen, in his recent History News Network blog article, “How Two Historians Responded to Racism in Mississippi”, provides a passage that captures the evolving subliminal mindset that permeates the judgment of racial encounters in our judicial system: “Logically, Bettersworth had to know that what he wrote about Reconstruction (and the rest of Mississippi history) in his textbook likewise made a difference in the present. He could not have believed that his textbook was only an innocent way to make a few thousand dollars without hurting anyone. At Mississippi State, he encountered the fruits of his labor in every class that he taught. He had to have known how appallingly racist some of his students could be. He had merely to talk with his own undergraduates, which I did when I was one. My best friend (!) at Mississippi State, for example, told me with pride what he had done when the black driver in front of him stopped suddenly for a red light in downtown Greenwood, and my friend didn’t stop fast enough. He jumped out of his car, surveyed the damage he had caused, then turned to the black driver and said, “Nigger! Why’d you back up?!” Knowing the mores of Mississippi, the African American dared not contradict a white man, so he drove off without getting the information needed to file an insurance claim against the driver who had hit him. Bettersworth’s state history textbook provided the intellectual justification for such outrageous acts of white supremacy. Most white students believed what his textbook said about the inferiority of African Americans. How were they to learn better? Southern society was structured to prevent them ever from having an equal interaction with a person of another race.”

The Black Residents of Nashville, in a petition to the Union Convention of Tennessee Assembled in the Capitol at Nashville, January 9th, 1865, provides the historical prologue that captures the morphed subliminal mindset of contemporary Grand-Juries in adjudicating contemporary racial encounters :

After making a strong plea for the franchise for blacks and the value of the black vote to restore the Union, the petitioners turned to another matter:

“One other matter we would urge on your honorable body. At present we can have only partial protection from the courts. The testimony of twenty of the most intelligent, honorable, colored loyalists cannot convict a white traitor of a treasonable action. A white rebel might sell powder and lead to a rebel soldier in the presence of twenty colored soldiers, and yet their evidence would be worthless so far as the courts are concerned, and the rebel would escape. A colored man may have served for years faithfully in the army, and yet his testimony in court would be rejected, while that of a white man who had served in the rebel army would be received. If this order of things continue, our people are destined to a malignant persecution at the hands of rebels and their former rebellious masters, … Every rebel soldier or citizen whose arrest in the perpetration of crime they may have effected, every white traitor whom they may have brought to justice, will torment and persecute them and set justice at defiance, because the courts will not receive negro testimony, …A rebel may murder his former slave and defy justice, because he committed the deed in the presence of half a dozen respectable colored citizens. … Is this the fruit of freedom, and the reward of our services in the field? Was it for this that colored soldiers fell by hundreds before Nashville, fighting under the flag of the Union? … Will you declare in your revised constitution that a pardoned traitor may appear in court and his testimony be heard, but that no colored loyalist shall be believed even upon oath? If this should be so, then will our last state be worse than our first, and we can look for no relief on this side of the grave. Has not the colored man fought, bled and died for the Union, under a thousand great disadvantages and discouragements?

Is there any wonder that in the establishment of racial apartheid in America, the Supreme court’s Plessy v. Ferguson’s (1896) ruling (“[I]t is not by reason of anything found in the act, but solely because the colored race chooses to put that construction upon it”) endures as this nation’s astigmatic vision of racial conflict.

Is there any wonder that in the establishment of racial apartheid in America, the Supreme court’s Plessy v. Ferguson’s (1896) ruling (“[I]t is not by reason of anything found in the act, but solely because the colored race chooses to put that construction upon it”) endures as this nation’s astigmatic vision of racial conflict.

We know how it all turned out. The pleas and testimony of the esteemed black leaders (in the eyes of blacks of that day) were dismissed by a consensus of “rational” white pundits and leaders as being overly emotional, and too dismissive of the obvious progress made in race relations.

Wesberry v. Sanders in 1964 declared our Human law on the franchise: “No right is more precious in a free country than that of having a voice in the election of those who make the laws under which, as good citizens, we must live. Other rights, even the most basic, are illusory if the right to vote is undermined. Our Constitution leaves no room for classification of people in a way that unnecessarily abridges this right.”

But the most devastating example of a contemporary bias in the “human practice” of our courts, which is intuitive to blacks but oblivious to a consensus of whites, is our court’s devaluing of black political testimony embodied in the judicial tolerance for the “practical construction” of State Voter ID laws. Our court justices have valued testimony pleading for redress from potential electoral fraud to address the ungrounded fears of a white electorate admittedly unsupported by any data, while the court has devalued testimony grounded in incontestable facts that Voter ID laws have a real, not a potential, disparate impact on a non-white electorate. If our courts have exercised such clearly astigmatic racial judgment in adjudicating our most precious political right in a democracy, the exercise of the franchise, is there in any wonder that our courts racially astigmatized political judgment has metastasized throughout our judicial system.

We can train the cops to value Black Lives, and ameliorate the injustice of being accosted by cops, but when accosted by prosecutors and grand jurors how do we restructure “the practical construction of American life” to value the testimony of non- whites to ameliorate the injustice of being judged.

If “history is prologue”, the witness I bear here , will be summarily shot down, and this testimony on structural institutionalized white misconduct will not be allowed to breathe in the discourse over a solution.