KCET

By Chris Clarke

December 22, 2015

December 15 is the birthday of Brazilian environmental activist Chico Mendez, who was assassinated at age 44 on December 22, 1988 in retaliation for his work to protect the rainforest. To honor Mendez, KCET’s Redefine is using this week to profile Californians whose work on behalf of the environment has been met with retaliatory violence.

On May 24, 1990, as forest activists Judi Bari and Darryl Cherney drove down Park Boulevard in Oakland on their way to an event in Santa Cruz, a bomb below Bari’s driver’s seat exploded, nearly killing her. Cherney, who was sitting in the front passenger seat, was also injured.

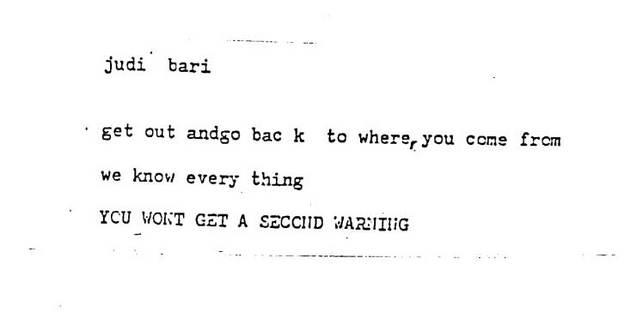

Bari and Cherney were working to build support for the Redwood Summer campaign, a grassroots effort to halt logging of some of the last remaining old-growth coast redwood forests in California. As Earth First! activists organizing in the tense timber towns of the North Coast, both had been the targets of previous threats. Bari had been a particular target of threats from what we’d now call violent trolls, in part due to her mixing labor activism with her environmentalism and in part because of her gender. On one occasion, a timber worker had run her car off a dark rural road.

The worst of those threats had been reported to police, who’d done little. When the crude pipe bomb exploded underneath Bari — and perilously close to a middle school bus stop — it must have seemed a logical culmination of those threats. But when the FBI arrived at the scene minutes later — an oddity — along with the Oakland Police Department, police arrested both Bari and Cherney on charges of transporting the bomb that nearly killed them.

It’s customary, when a journalist writes about people he knows personally, to admit as much in a “full disclosure” statement that smacks vaguely of contrition. I can’t do the contrition part: I was proud to call Bari a friend. I met her a few days after the bombing as she lay in her bed at Highland Hospital. I was part of a volunteer security detachment organized by forest activists; we took turns sitting outside her hospital room screening visitors. Even gravely injured and officially in custody as doctors assessed the damage and her chances of recovery, Bari continued to receive threats.

Judi was a source of inspiration and encouragement in my life and work for the next seven years, and I miss her.

Death threat received before the bombing | Screencap: judibari.org

Things were hot in the redwoods in 1990. As described in our earlier piece on David “Gypsy” Chain, timber corporations had for several years sped up the rate of clearcutting old-growth trees on both public and private land. Logging was so accelerated that some timber workers started suggesting they were cutting themselves out of jobs just a few years down the road.

Opposition to the logging in California took many forms, from sabotage to non-violent civil disobedience such as tree-sitting, to formal political approaches such as Proposition 130, the “Forests Forever” initiative, which made it onto the ballot in the November 1990 election. for the previous two years Bari had organized successful campaigns to save old growth in places such as the now-protected Cahto Wilderness Area.

In 1989 longtime peace activist Fred “Walking Rainbow” Moore had suggested that nonviolent activists converge on the redwoods in a campaign reminiscent of the Mississippi Freedom Summer, to put their bodies on the line to stop the cutting of the old growth. The seed of his idea fell on receptive ground, and a groundswell of North Coast and Bay Area activists began to make the campaign a reality. First called “Mississippi Summer in the Redwoods” but hastily re-branded as “Redwood Summer,” the plans for massive demonstrations and widespread civil disobedience attracted increasing attention worldwide. Local environmental groups signed on, as did Earth First! and the Industrial Workers of the World, which sought to unionize loggers to advocate for the long-tgerm sustainability of their own jobs.

In the first days after the car bombing, with Bari struggling to survive in Oakland’s Highland Hospital and a bandaged Cherney in the custody of the Oakland Police Department, the future of Redwood Summer seemed uncertain.

Both Bari and Cherney were non-violent activists. Bari had achieved renown — if not universal popularity within an occasionally macho Earth First! — for eschewing a form of sabotage called “tree-spiking,” in which activists drove large nails into the trunks of trees in danger of being logged. The idea was that a spiked tree could cause expensive damage to blades in sawmills, and that timber companies would thus be reluctant to cut down spiked trees. Timber workers, justifiably enough, saw themselves as potential collateral damage if their mill saws or chain saws ran into a spike. A timber worker was way easier and cheaper to replace than an expensive band saw.

Bari, who’d started her activist career in the postal workers’ union in Maryland, was innately sympathetic to the concerns of timber workers, and pressed both workers and forest activists to find common ground. Cherney, who had found his way into Northern California eco-activist circles as a folksinger, was far gentler and more conflict-averse than Bari.

The idea that either Bari or Cherney would have knowingly transported an Improvised Explosive Device for any reason was preposterous on its face to anyone who knew either of them. To those of us familiar with the context, Judi and Darryl’s arrest smacked of nothing less than COINTELPRO-style dirty tricks on the part of law enforcement.

That impression was bolstered by the unnerving discovery, some years later, of the fact that the FBI had held a “bomb school” for law enforcement on a Louisiana Pacific clearcut in Humboldt County just four weeks before the bomb exploded in Bari’s car. The “school” was intended to train first responders in dealing with the immediate aftermath of a car bombing. Three cars were bombed during the school, each with a pipe bomb in the passenger compartment, despite instructors’ statements that such bombs were more usually placed in the engine compartment or attached to the underframe.

At least four of the bomb school participants were first responders at Park and Macarthur on May 24, including the school’s instructor, FBI Special Agent Frank Doyle, who told arriving responders “this is your final exam.”

Bari and Cherney wouldn’t find out about the Bomb School for some time after the bombing. But there were other facts that came to light earlier on that poked holes in the OPD and FBI’s case against the activists.

One arose just two weeks after the bombing, two weeks during which newsmedia had dutifully repeated the police’s charges that Bari and Cherney were transporting a bomb that had gone off unexpectedly. That fact took the form of a letter to reporter Mike Geniella of the Santa Rosa Press Democrat whose author, signing him- or herself as “The Lord’s Avenger,” took credit for the bombing. The letter claimed that the bombing was in retaliation for Bari’s presence at a counterprotest confronting anti-abortion activiists outside a Planned Parenthood in Ukiah.

The letter also provided credible details about the bomb’s that construction and placement that weren’t yet known to the public, and descriptions of a similar bomb that was set outside a timber mill in Cloverdale.

The Cloverdale bomb didn’t work as planned. The bomb in Bari’s car almost did. The bomber had filled 11 inches of 2-inch galvanized pipe with explosive, and sealed each end with a metal end cap. A fuse ran from a hole in the pipe (epoxied shut) to a 9-volt battery, the circuit for which included a pocket watch timer and a motion-activated switch using a ball bearing and bent wires. Once the timer went off — a maximum of 12 hours after being set — any motion sufficient to cause the ball bearing to move and close the circuit would detonate the explosive. To maximize the explosion’s shrapnel, the bomber coated the outside of the galvanized pipe with finishing nails.

Fortunately for Bari and Cherney, one of the bomb’s end caps came off, directing most of the force of the explosion out the driver’s side door. Had the bomb worked as intended, it’s hard to imagine either Bari or Cherney would have survived.

Despite the initial charges that Bari and Cherney were knowingly transporting the bomb, it’s hard to imagine what circumstances would cause them to arm a bomb of that design while it was being transported.

The FBI’s Frank Doyle and the Oakland Police Department initially told media that the bomb would have been in plain sight in the passenger foot well behind the driver’s seat, and that Bari and Cherney would thus have known it was there.

But the evidence blew a literal hole in the police case against Bari and Cherney, and charges against the two were dropped seven weeks after the bombing.

That bit of evidence, an Oakland Police Department photo of Bari’s car, was reproduced hundreds of times in environmentalist media when it was made public some years later. The photo showed that there was no way the bomb could have been in the rear footwell of the car: the hole blown by the explosion was directly under Bari’s driver’s seat. Even with the end cap malfunction, it was a wonder that she survived.

Judi Bari’s Subaru with a hole exploded in the floorboard beneath the driver’s seat. | Photo: Oakland Police Department

Bari survived her serious injuries, and became even more outspoken, writing and organizing to save the redwoods until cancer took her life in 1997. She was survived by two young daughters. Before she died, she and Cherney filed suit against the FBI and OPD for violating their civil rights by pursuing an unsupported criminal case against them. In 2002, a jury found for Bari and Cherney, and ordered Frank Doyle, two other FBI agents, and three Oakland police officers to pay Bari’s estate and Cherney $4.4 million, after a trial mainly characterized by the OPD and FBI blaming each other for the investigation’s myriad screwups.

Among those screwups: the bomber has never been found, though suspects publicly accused by observers range from Bari’s ex-husband to a couple of activists in the sometimes fractious North Coast progressive community. Bari often quipped that she wished the FBI would “find the bomber and fire him.” The possibility that the bombing was part of a COINTELPRO-style intervention into forest activism hasn’t been ruled out, nor has the possibility that the bomber was a freelance right-wing terrorist like the Lord’s Avenger claimed to be.

Darryl Cherney’s activism continues, as has his work to preserve Bari’s legacy. In 2012 Cherney worked with filmmaker Mary Liz Thomson to produce a film about the bombing and the court case that followed. The film, “Who Bombed Judi Bari?” asks a question that goes shamefully unanswered. To this day, law enforcement continues to obstruct efforts to examine the forensic evidence from the bombing that could reveal who tried to kill Bari and Cherney.

That would-be assassin failed, and Bari spent the rest of her life working to save the redwoods. Cherney continues that same work, and activism in other fields, to this day.

As for Redwood Summer, whether or not it was a success depends on your definition. Stunned and angered by the attempted assassination, activists poured into North Coast demonstrations and actions over the summer. There were hundreds of arrests, almost 150 in Humboldt County alone. Activists remained scrupulously nonviolent, a commitment not always shared by occasional egg-throwing timber industry sympathizers.

And yet the logging continued, sometimes at a faster rate in an explicit attempt to cut trees before Proposition 130 brought new, more stringent regulations to California forests. That rush was pointless: Prop 130 lost by more than 300,000 votes. On occasion activists were arrested defending a stretch of redwoods, spend a couple days in jail, be released on their own recognizance, and find the trees they’d been arrested to defend had been cut.

But from the perspective of a quarter century, when it came to educating Californians at large about the importance of intact redwood forests, Redwood Summer was an unqualified success, even if it took a couple years for the lesson to sink in. That’s a victory well worth savoring, and it might not have happened without the work of Bari and Cherney — before and after the attempt on their lives.

Follow the money is a basic rule of crime investigation. A consortium of logging corporations had a multi-billion-dollar motive to defeat the Prop. 130 logging reform initiative on the November 1990 California ballot. Their line was “Defeat the Earth First initiative, it’s too extreme!” The Bari bombing happened at the end of May 1990, perfectly timed to form the basis of the loggers’ campaign and to try to derail Bari’s Redwood Summer movement which would call attention to the liquidation logging of ancient redwoods. The industry did use the Bari bombing and media smear campaign to defeat the initiative, and reaped at least $4 billion in profits over the next decade as a result.

The timber consortium hired one of the world’s biggest PR companies, Hill & Knowlton, to oversee the anti-initiative campaign. H&K is the company that engineered public consent for the Gulf War I invasion of Iraq by creating and distributing a false story about brutal Iraqi soldiers dumping newborn babies out of incubators in Kuwait. H&K represents national governments and large corporate interests, and they play hard ball in their tactics for shaping public perception and opinion in their clients’ interest.

My personal theory of the Bari bombing is that it was a cooperative PR effort by H&K and the FBI to do a COINTELPRO style hit on Bari. They used a pipe bomb that could be plausibly claimed to be home built by Bari or an accomplice. The FBI was at the bomb scene so quickly that Bari quipped that they must have been hiding right around the corner with the fingers in their ears. There was a six-week sustained media smear campaign dribbling out false claims of evidence that Bari was complicit in her own bombing, and was an “ecoterrorist” who intended to blow people up with the bomb. I attended every single day of the six-week trial in Bari’s civil rights suit against the FBI and OPD. There was no evidence showing Bari was in any way to blame for the bombing.

The sham investigation of the bombing focused entirely on the environmental activist movement. There has never been a real police investigation into who was behind the Bari bombing, or who would benefit financially from it. There’s a good reason for that if such an investigation would show police, FBI and timber corporations were behind it.

Read a detailed history of the case at www.judibari.org