Jacobin

By Jon Flanders and Peter Lavenia

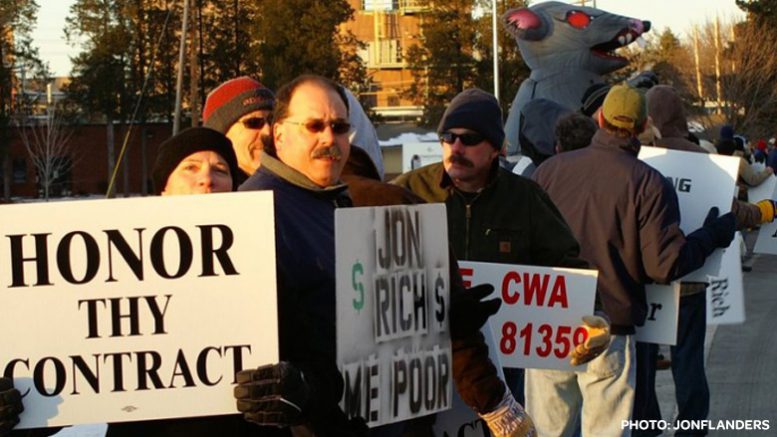

In the fall of 2016, a group of chemical workers decided to go on strike. About seven hundred largely white and male members of IUE-CWA Local 81359, located in the small upstate town of Waterford, New York, suddenly drew attention from labor, the Left, and national media as the 2016 election came to a close.

At a time when media attention had turned to the “forgotten” rural industrial workers whom both Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump courted in the sagging small towns of the United States, the rowdy picketing and glowing burn barrels of this strike made headlines far beyond Waterford.

With labor’s power near an all-time low, any example of organized workers eking out a victory is worth examining. And Momentive strikers’ tactics were the old ones of militancy, solidarity, and political independence. Their success shows that these tactics can still work — even among a group of workers who might sympathize with the rising right-wing populism of Donald Trump.

The Seeds of Struggle

The origins of the Momentive strike go back more than a decade, when General Electric decided to rid itself of the plant as part of a restructuring initiated by CEO Jack Welch. Business Insider notes, “As CEO, Welch facilitated a massive reorganization plan, spinning off roughly 200 businesses and making 370 acquisitions, while drastically cutting down the size of its workforce.”

Momentive was sold in 2006 to the private equity firm Apollo Management, which quickly instituted a drastic wage cut in the middle of a 2008 contract period. The next several contracts found the workers increasingly oppositional, and the workers’ votes opposing the contracts climbed higher and higher.

The union traces its origins back to the CIO’s United Electrical Workers. But when the McCarthy-inspired anticommunist purges of labor took place in the 1950s, the local was part of the new, conservative International Union of Electrical Workers (IUE). This affiliation proved an enormous obstacle to successful organizing. IUE officials have been missing in action any time shop-level action has been called for by the local.

The union traces its origins back to the CIO’s United Electrical Workers. But when the McCarthy-inspired anticommunist purges of labor took place in the 1950s, the local was part of the new, conservative International Union of Electrical Workers (IUE). This affiliation proved an enormous obstacle to successful organizing. IUE officials have been missing in action any time shop-level action has been called for by the local.

A merger with the Communication Workers of America (CWA) in 2000 created a new hybrid international, IUE-CWA. The Momentive workers found some benefit from the CWA, which has a more strike-friendly activist orientation and history, particularly in the telecommunications industry. The leadership of the Momentive local, Local 81359, eagerly participated in CWA meetings and actions up to and including the 2016 Verizon strike.

After the 2009 wage cuts, Local 81359 leaders sought out advice and support from the regional AFL-CIO labor councils. Some of the activists in these councils were supporters of the Labor Notes tendency in the labor movement. Leaders of the Momentive local had attended Labor Notes conferences and soaked up whatever advice and counsel they could get from attendees.

Labor Notes policy member and former CWA staffer Steve Early was invited to address the workers. They learned the importance of extending solidarity to other workers battles and became familiar figures on picket lines around the Capital District region. This would become a major factor when the Momentive workers went on strike themselves.

In 2011, the local carried out a grievance strike against the company, a strike resulting from an impasse between workers and management after exhausting all options outlined in the workers’ contract. (The ability to strike over a grievance dates back the CIO and the United Electrical workers. In the early days of the CIO, the right to strike over grievances that were not resolved by management was seen as necessary by the rank-and-file insurgents that built the industrial unions. Most unions have given up this tactic, as resolving grievances is more and more seen as a task for union staff to accomplish through bureaucratic maneuvering rather than the membership through workplace action.)

For the first time, the workers got a chance to feel their power as the plant shut down during a winter cold snap. Again, their international representatives from the IUE were nowhere to be found during this action.

The Troublemakers

In 2011, workers occupied the Wisconsin state house against the anti-labor regime of Gov. Scott Walker; Occupy Wall Street followed a few months later. Momentive workers were among those who traveled to New York City to support the Occupy movement. IUE-CWA President Dominick Patrignani was part of the protest when Occupy Albany was shut down. One of the members of the local was arrested during the May Day march that followed largely organized by Occupy Albany.

In 2013, Local 81359 voted down a concessionary contract by a substantial margin, but the votes of three other small locals — one a technicians local in the Waterford plant, the others in small plants in the Midwest covered by the agreement — were enough to pass it, 357 to 348.

Following a familiar pattern for private equity firms, Momentive filed for bankruptcy in 2014 and won a decision in court widely reviled by bond holders that shorted senior debt owners and favored Momentive. They objected to a portion of the plan that allowed the company to emerge from bankruptcy while paying off senior bondholders with new debt at below-market interest rates; they claimed this violated the rights of senior bondholders who should have been paid in full.

This outcome could have made Momentive management more friendly to its workforce. It didn’t. Local 81359 was in the Momentive management’s crosshairs as the trouble-making bargaining unit. And a confrontation was inevitable.

It came in late 2016. After bargaining ran over the deadline for the contract’s expiration, the tentative agreement that was reached over the objections of the Local 81359 leadership was voted down, despite the votes for it by the smaller locals. This time, the members of the Waterford plant’s seven-hundred-member-strong local were able to prevail, and the strike was on.

On November 2, as we watched the workers flood out of the plant and onto the picket lines there was an immediate sense that this was not an ordinary strike. Rebellion was in the air as masses of workers surrounded trucks near the plant.

Over the course of the strike, with other plants down a side road from Momentive, the workers constantly interrogated truck drivers to see where they were headed. One of the strikers was so angry after getting bumped by a truck that he laid down in front of it. As a result, he was fired, one of twenty-six workers disciplined during the strike. Yesterday, the union announced that it had reached an agreement with the company with twenty-five of those workers, with sixteen of them returning to work, five retiring, and four coming to severance agreements. The twenty-sixth worker is still in negotiations with the company.

The feeling of rebellion persisted in the days following as mass picketing continued at the nine factory gates. A large, hand-painted sign at the diner across from the plant expressed an Occupy-inspired sentiment: “We are the 99 percent and we have had enough!”

In fact, the strike took on a genuine Occupy Wall Street feel, as unions and community groups flocked to show support. This feeling was creatively used by the union in trips to New York City to picket the headquarters of Apollo Management and in a memorable visit to the wealthy neighborhood of Momentive CEO Jack Boss.

Solidarity actions came from religious groups, gifts of food from the Islamic Center of the Capital District, and bread from Green Party baker Matt Funicello. A largely African-American contingent from Citizen Action joined an evening picket line. A stream of elected officials and members of other union locals visited the picket line. So many gifts for children were donated at Christmas time that the union had to find other groups to take them.

Solidarity actions came from religious groups, gifts of food from the Islamic Center of the Capital District, and bread from Green Party baker Matt Funicello. A largely African-American contingent from Citizen Action joined an evening picket line. A stream of elected officials and members of other union locals visited the picket line. So many gifts for children were donated at Christmas time that the union had to find other groups to take them.

As the weather turned colder, burn barrels and hastily improvised, shanty town-style shelters sprang up at the nine gates where workers were picketing. The stretch of NY Route 32 in front of the plant was full of life as the workers came and went while passing cars honked continuously in support.

The political energy this time was not coming from the youthful post-graduate sector so prominent in Occupy Wall Street. This magnetic focal point of struggle was driven by a largely white, rural-suburban, male, and “middle-class” workforce. The skilled and semi-skilled working class making wages that with overtime put them in the very economic strata that supported Trump — and indeed, many of them did and still do.

In fact, the national and international press — a cover story in the New York Daily News and a piece in the Guardian — ruminated about the Momentive Trump-supporting workers finding themselves in a war with Trump allies. Despite the Trump leanings of the workers (most of whom initially supported Sanders before going over to Trump, according to President Patrignani), this strike turned out support from a true diversity of sectors. To quote a tweet by Jacobin editor Peter Frase after he visited the strike: “Class struggle trumps hate.”

After 105 days, as supporters got better organized and formed a strike support committee that regularized Saturday solidarity pickets, the strike ended — though still with a significant number of votes against the tentative agreement. The argument for the “yes” vote was that while there were concessions in the contract, enough of the negative demands of the company had been beaten back to justify ending the walkout.

The union members on both sides of the vote found common ground in a campaign to get the twenty-six workers fired for various picket line incidents and allegations of sabotage rehired. An initial rally for the twenty-six generated a big turnout, and attendees’ mood was far from defeated.

In the time of Trump and Brexit, with reactionary parties on the march in the advanced capitalist world, the Momentive strike gives us a glimpse of a future in which the working class now courted by the Right can still be seen as a force for revolutionary change.

Broad Solidarity

The choices made by workers in their fight against the ruling class never occur in a vacuum, but rather are conditioned and constrained by the structure of the system. The tactics developed at Momentive show us that road. Most of them aren’t considerably different from the kind of tactics unions have used throughout the history of the labor movement; Momentive showed that the old stuff still works.

The most important tactic, of course, was the strike itself. The strike at Momentive made the class struggle tangible: workers and allies on one side of the line; bosses, scabs and police on the other. Many young activists from the community and farther afield who joined the picket lines said that seeing workers that most dismissed as too old, white, and conservative in open revolt against corporate America was eye-opening. Workers, meanwhile, were exposed to radical ideas, mingled with allies from all walks of life, and got a taste of their power as an organized and collective force.

This was most apparent in two places: the picket line, where striking workers walked alongside community activists, members of political groups such as the Green Party, Socialist Party, and the Democratic Socialists of America, along with environmental advocates and single-payer health care supporters, and the “Hot Dog Headquarters,” set up across the street from the line in an old diner building, where workers and community supporters would mingle, discuss ideas, read political literature, and eat food made by fellow workers and often donated by community members.

Also crucial was the broad-based solidarity the strike received. A local strike support committee sprang up almost immediately that brought together an array of parties, groups, and individuals all committed to aiding the striking workers. The committee reached out to a local Islamic center, single-payer advocates, local businesses, environmentalists, and students, among others. The committee’s membership did not agree on everything, but they were united in an aim to aid the strikers.

During the strike, tangible class demands created a functional and binding alliance between groups that would otherwise have had little to do with each other. In working together without ceding organizational independence, the committee created the possibility of a stronger class-oriented organization in embryo. The aforementioned collection of groups like the DSA, Green Party, and Socialist Party that would otherwise likely remain separated by a gulf over political tactics came together around a common cause of supporting strikers.

Committee members organized protests, solidarity actions, wrote press releases and editorials together, and formulated a joint strategy to aid the Momentive workers. The possibility of a broad-tent coalition — or even what a future workers’ party might look like, with various factions that cooperated on large issues even if they did not agree on everything — was apparent when the committee met at local diners and pubs near the picket line.

The strikers and support committee welcomed politicians to walk the line, but they saw themselves as independent from the political parties and forces supporting them while marching together for a common end. Openly socialist groups marched on pickets alongside Momentive strikers without incident.

By remaining outside political party influence, they were able to focus on class demands, retain the possibility of political radicalism, and build their own organization. Local elected officials spoke, but were urged to prove their solidarity with workers beyond words by using whatever power they had to aid the strikers.

Political independence also meant the development of political consciousness could occur outside the framework of the major parties and their adjuncts. It seemed clear that workers were willing to take seriously the people and groups who participated because they were not there to turn the picket line into a recruitment center. The civility among the participating organizations continued because there was a greater goal than group growth.

The strikers made tangible economic demands as workers on the company that owns Momentive. These demands united workers regardless of their political registration or ideology. Many workers had voted for Bernie and/or Trump, but the strike gave an entry point for raising class consciousness and to combat racism and xenophobia.

For example, a debate on one of the workers’ Facebook pages erupted over racist comments made to African-American scabs by picketers. Shortly afterwards, the practice ended. It was a small example of how class demands can unite a group of diverse workers and, in the context of that unity, individual workers’ racism can be challenged.

The strike moved beyond simple rallies to incorporate a visit to the CEO’s neighborhood in nearby, and very bourgeois, Saratoga Springs, as well as multiple visits to New York City in order to protest outside the corporation’s headquarters alongside allies from New York unions and single-payer advocates. The workers went beyond controlled protest and its limited efficacy.

During the visit to Saratoga Springs, the workers went door to door to Momentive CEO Jack Boss’s neighbors with a flyer outlining their issues with him. The national press soon began to take notice.

One neighbor, an investment banker, sought to provoke a confrontation with the flyering workers. This backfired when the local sheriff’s threw him up against his car rather than going after one of the strikers — producing a front-page headline on several local papers, delighting the workers.

Choosing Differently

Unions are currently the weakest they have been in a century. The situation looks bleak for workers. But with that weakness comes new opportunities. In the coming years, the structural barriers to class organizing will be further weakened: the decay of the Democratic Party and the old union bureaucracy may open the field to radical organizing among workers. Even if our organizing today looks little like the forms of organizing of the past, the possibility for domestic, class-based political growth has returned.

Political independence, class-based demands, radical ideology, and broad-based solidarity are all possibilities for the future. As in past periods of upsurge, there are strong mitigating factors against this radicalization. But workers, like the Momentive strikers, can choose differently.

Jon Flanders retired in 2013 from the CSX railroad and is a member of IAM Lodge 1145 in Selkirk, New York.

Peter LaVenia holds a PhD in political theory from the University at Albany, SUNY. He is currently the co-chair of the Green Party of New York.